Commonplace representations of bureaucracy (those that usually cross the minds of people not doing any bureaucratic work) make it look like a meaningless (because dull, repetitive and boring) activity. For most people, bureaucracy is as grey and empty as it can get. Though widespread, such commonplace representations can be shown to be wrong.

Jean Tardieu (1903-1995), a French theatre writer (and also musician and poet), manages to effectively challenge the idea that bureaucracy is meaningless in a play written in 1955, titled Le Guichet (best translated as The Counter). The play has four characters: the Clerk (le Préposé), the Client (le Client), the Radio (la Radio), the Loudspeaker Voice (La Voix du Haut-Parleur) and the Diverse Noises Outside (Bruits Divers Au-Dehors). The presence of some non-human characters (such as the Diverse Noises Outside) is one of the distinctive characteristics of Tardieu’s theatre. The play itself is part of a trilogy, called The Triple Death of the Client (La triple mort du client), along two other plays, namely The Lock (Le serrure), which tells the story of the client of a brothel and The Furniture (Le meuble), telling the story of an invisible client who wants to buy a piece of furniture.

Tardieu is often associated with the theatre of the absurd (that was becoming a big thing in the Frances of the 1950s). Be that as it may, The Counter is, at least in my reading, mostly a play about how apparently meaningless activities such as being a clerk or street-level bureaucrat working at a counter are actually filled with meaning.

There are two ways in which Tardieu’s play points toward the meaningfulness of bureaucratic work. The first one is pretty straightforward: we see the Clerk working in an environment that is deeply personal and, as such, makes sense to him. As the play begins, the Clerk is ‘reading silently while scratching his head with a letter opener’. And while the Client is waiting for his number to be called, the Clerk comfortably moves behind the closed counter, opens the radio and listens to a song interpreted by a crooner (‘chanteur de charme’). Tardieu does not specify who the singer is, but I’d like to think it’s Yves Montand, one of the most famous French crooners ofthe 1950s. Now, considered as a whole, this working environment points to the meaningfulness of intimate offices, the kind of offices that you can make your own and where you can feel at home. Pace representations that portray bureaucratic environments as dull and grey, this Clerk’s office has nothing bleak or boring.

Yves Montand. C’est si bon, recorded in 1948 (I like to think this is the song the Clerk is listening to)

The second way in which bureaucratic work conveys meaning is somewhat less obvious. It comes up as the dialogue between the Client and the Clerk unwinds. Their conversation begins quite tediously and is limited to technicalities: noting down the Client’s name and place of birth, the Client inquiring about the timetable of the train (as there is some suggestion that the counter might be place in or close to a train station and might be more of an information desk). But the conversation then shifts to deeper issues, like predicting whether the Client is going to meet his loved one that very day (the Client thinks that the Clerk can help with this). The conversation eventually steers toward pure metaphysics, when the Clerk tells the Client that he can take him on an imagination trip to a place that is ‘farther than the end of the world: where the forms become ideas, where beings are only essences, where still clarity reins and where there is an equilibrium between a future that has already passed and a past that is becoming’. This might sound like mumbo-jumbo, but it might also have had some meaning to the philosophically sensitive French intellectuel of the 1950s. The conversation reaches its peak (and end) when the Client asks the Clerk ‘when will I die?’ and the Clerk answers ‘with a very polite and awful smile’ that death will come ‘in a few minutes’, after leaving the counter. This, I think, points to a deeper (if not always obvious) dimension of bureaucratic work, which is that a lot in our lives – how well we do in day-to-day activities, the kind of services we have access to when managing our health, safety or, more simply, when asking for useful information about public transport – is often pervasively influenced by how well bureaucracies function and by the quality of the decisions that they make. In that sense, the quality of bureaucratic work is the quality of our lives and, as such, cannot be more meaningful than it already is.

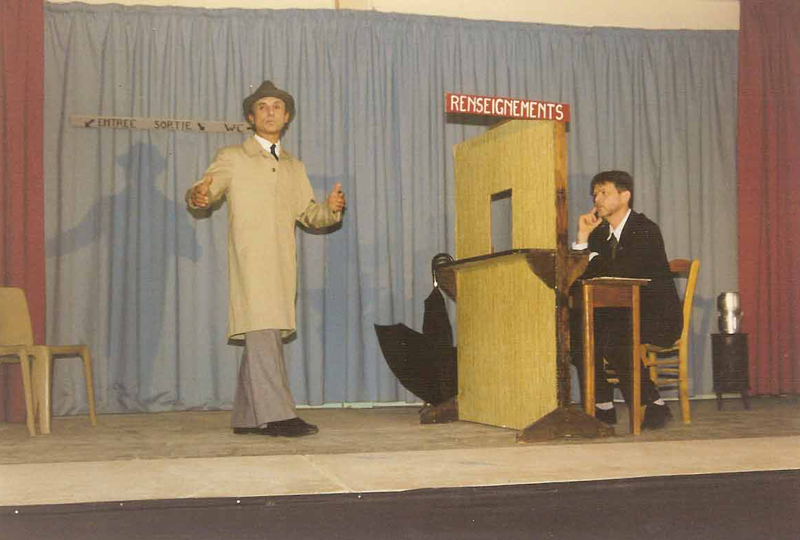

Representation of Le Guichet by the theatre company Les Polykandres in 1997

(see link to the company activity here: http://www.fr-montaut-les-creneaux.fr/theatre/theatre.html)

Leave a Reply