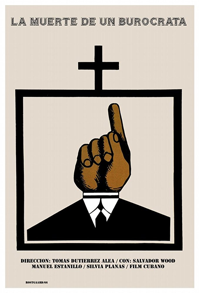

(Note: this is a guest post by Caterina Preda presenting the movie The Death of a Bureaucrat (1966) by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea)

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea is one of the best-known filmmakers of the post-revolutionary Cuban cultural landscape. In several of his films, he discusses the problems of the new revolutionary society and criticizes the remainders of the pre-revolutionary period. One such example is the film Death of a Bureaucrat (1966), released seven years after the victory of the Cuban revolution and, as the director acknowledged, expressing his own experience in confronting the absurdities of Cuban bureaucracy and their opposition to the professed revolutionary ideals.

The film targets Cuban bureaucracy, but its underlying critique could also be relevant for other national bureaucracies. For 1 hour and 25 minutes, we follow the protagonist of the film, the nephew of Francisco J. Perez (or Paco, for short). As Paco is buried, the first scene shows the speech of his boss. The boss speaks about Paco’s life, who was a proletarian, ”a paradigmatic patriot”, and praises him for having invented a machine to speed up the production of revolutionary busts of José Marti. (warning: spoilers ahead)

The real story begins with the nephew and the wife of the deceased wanting to obtain Paco’s pension and being asked for Paco’s union card. The problem is that the proletarian hero was buried with his union card. In his attempt to settle the situation, and in appealing to the authorities of the cemetery, or of the different institutions to which he is sent to, the nephew ends up being a felon, becomes mad and kills the director of the cemetery.

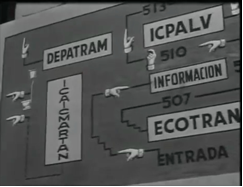

Faced with the authorities’ inertia for two years, the nephew decides to exhume the body himself. Once that is done and the union card is retrieved, he needs to burry his uncle a second time. But doing so means that he needs to get different papers signed by yet other local authorities. One of the best illustrations of his attempts to resolve the situation shows him being redirected by men seated at tables in a huge hall where one can hear the sound made by typing machines from table number 2, to table number 22, then table number 46, only to return to table number 2 where his judiciary order is typed by the first bureaucrat he met. Afterwards, to speed up the process, he is sent across the street to the “Department of speeding up formalities” (DEPATRAM) to get his order stamped. He waits in an endless row. Here, when his turn comes, the alarm goes off, and the employee puts on his sunglasses and walks away because his work day is over.

Another very interesting image is that of the administration preparing the campaign to fight bureaucracy under the slogan “Death to bureaucracy”, with the image of a fist crushing bureaucracy. For the campaign, the proletariat is represented by a young woman in a bathing suit holding a hammer with which she is prepared to hit the head of bureaucracy.

Despite the campaign, bureaucracy remains solid and can’t be stopped. When Paco needs to be buried again, the nephew is faced with a refusal from the director of the cemetery. What ensues is a general fight between the cemetery representatives, the funeral house representatives, and other relatives who arrive at the cemetery. In the end, the nephew thinks he has all the required papers and signatures and goes to the cemetery to bury his uncle. The director of the cemetery still doesn’t understand the situation. Faced with the absurdity of an inert administration, the nephew, mad with rage, beats and ends up killing the director of the cemetery.

Confronted with an absurd administration, the nephew can only bend the rules to get out of the impasse. In the process, he turns crazy, and resorts to murder. His uncle, the model worker and the proletarian patriot can also be seen as the postmortem victim of the administrative system. The labyrinth of bureaucracy, as well as the emptiness of endless formalities are decried in a satirical tone by Gutiérrez Alea, and, arguably, his portrait could be translated to (almost) any other political context besides that of revolutionary Cuba.

(Written by Caterina Preda, Senior Lecturer, PhD, Department of Political Science, University of Bucharest)

Leave a Reply